In the 13th Century, the kings of Hungary encouraged settlers, mainly farmers and merchants from the Rhineland, to settle in what we know as Transylvania. These Saxon settlers were given special social and economic status, a treatment they guarded jealously through the centuries that followed and the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

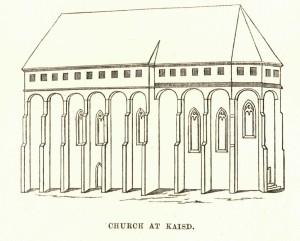

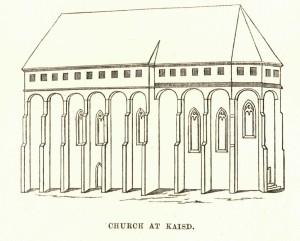

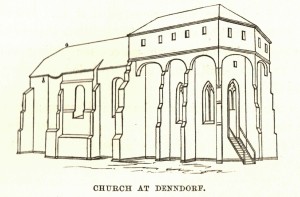

Note the high windows from which defenders could fire, and the arches above the buttresses, behind which were openings allowing things to be dropped or poured onto attackers.

The areas they settled were remarkably abundant, and the towns and villages they founded were very often quite rich – able to bear the occasionally huge taxes imposed on them first by their Hungarian and then Imperial rulers, who treated their Transylvanian territories as a bank account to be dipped into in times of trouble with scant regard for the effect on their subjects. In the founding of Promethea, that history was played on to great effect by Frankenstein and his allies. The chance to throw off the onerous weight of ‘absent landlords’ and to truly forge their own destiny appealed greatly to the Saxon spirit.

The settlers had other concerns beyond their Hungarian rulers. As a border country, they were in the firing line. They suffered sporadic invasions from Tatars in the 16th to 17th Centuries, and from the Ottoman Empire, who had eyes on the holdings of the Austro-Hungarians. As a result, the most successful Saxon settlements were the most fortified. This also applied to their churches.

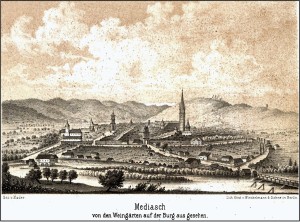

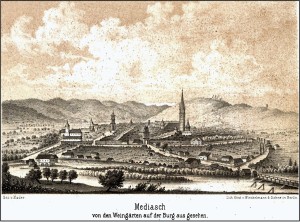

In the mid-1860’s, English writer Charles Boner stayed with the Protestant clergyman responsible for the fortified church at Mediasch – modern day Medias in the county of Sibiu.

A drawing of Medias from around the time of Charles Boner’s visit.

“The church is surrounded by three high walls, flanked with towers, and a low, pointed, arched portal leads from one to the other. In almost every Saxon village there are similar evidences of the danger in which men lived in earlier times. They went to rest at night in perfect peace, and at morning perhaps, when the streaks of dawn were just appearing above the hill-top, there, too, would be seen wild and barbarous hordes, waiting in the twilight to descend upon their prey. Many an every-day arrangement, even, tells us of the fear which regulated their acts. There was a time, for example, when the early service was postponed till a later hour, – it not being thought safe to open the gates of the stronghold in which the church stood in the dim light of daybreak, lest the enemy, taking them by surprise, might force his way in. In some churches I have seen the large round stones still standing on the parapet of the tower, as they were placed centuries back to hurl down upon the besiegers, when the outer walls were taken, and, all being lost, the inhabitants were attacked in this last place of defence.”

Stones were not the only thing Boner found on standing, a little breathless, on the high walls of these bastions:

“Besides these still remaining from old perilous times, I have seen rusty halberds and clumsy fire-arms, fitted only to fire from behind the wall.”

Boner mentions that his research reading spoke of warrior pastors, whose effects could include cup, cassock, and suit of armour.

This is a nice shot of (what I sincerely hope is) the fortified church Boner stayed close to in Medias.

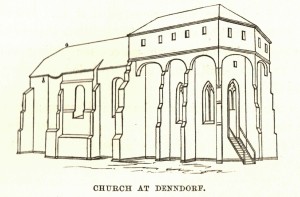

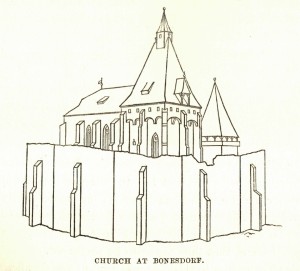

The Saxon fortified churches were built not on the orders of some local landed dignitary or princeling lord. These were structures built by the burghers for their own protection. There was no standard plan, with local conditions and available resources defining the look of the church. In general terms, though, these buildings were stocky, solid, and largely unadorned:

“The view to defence also was a reason why solidity was preferred to ornament; and why, in these Saxon fortified churches, we find all broad, strong, firm, and wholly destitute of that decoration which in other lands church architecture always presents.”

Note the very easily defendable main entrance.

The lack of useable sandstone was another reason for the scarcity of fancy flourishes. What there was was needed for the main construction and the walls. So scarce was quality building material that nearby Roman ruins were enthusiastically plundered, adding Roman columns and other ‘ornamentation’ to buildings that otherwise had none. Only the bell tower and font, as Boner points out, might be given a little more careful attention, and both because of their importance. The former in particular was especially vital – in event of the alarm needing to be raised, and help called from neighbouring settlements, it was the church bell that needed to be used.

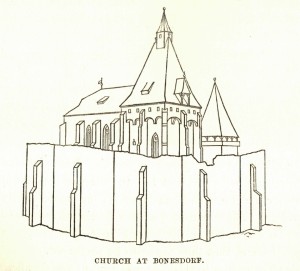

Sometimes, all you need is a wall. A really big wall.

The churches were fortified by surrounding walls, towers, bastions, and even moats and bridges. Storehouses were abundant. Even when Boner visited, many villages had never lost the habit of storing their produce in the structures in and around their church sanctuaries. The churches themselves were internally first and foremost designed for defence, despite also being places of worship. Buttresses were stout and heavy, arched at the top, and defenders within could drop stones, throw and fire weapons, and even pour flaming pitch down on any attackers at the walls. It was not unheard of that the most exposed walls had no windows or doors at all.

For the military of Promethea, these churches were both an opportunity and a threat. Each was a ready-made fortress, and no few were used as such, forming the administrative centres for military bases and the like. The unoccupied ones presented an issue. Too central, too obvious to be used as resistance bases, they nonetheless were a security risk. As a place for a last stand, they must have been tempting to say the least.

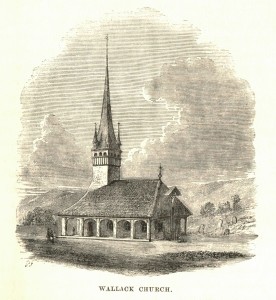

Far less defensible, the wooden churches of Wallachia were certainly not impregnable fortresses.

References

Many of these unique structures remain today, and a number have been given due recognition as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The link includes a lovely video showing some of the defences. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/596

Boner, 187 to 197 and elsewhere.

Tatars in Transylvania: http://www.academia.edu/8345838/A_Legend_about_the_Tatars_in_Transylvania

Some beautiful pictures of Transylvania, including the fortified church at Biertan, one of the UNESCO churches: https://smilewanderer.wordpress.com/tag/transylvania/

A modern picture by Jacek Brejnak of the fortified church at Saschiz (Boner knew it as Kaisd, see above), another of those selected by UNESCO, now standing beside a tower built in the 1830’s that Boner chose to ignore: http://www.panoramio.com/m/photo/95114674#