History of Promethea

European history of the mid-1800s is hugely complex morass dominated by the gradual disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the troubled birth of nation states such as Germany, Italy and, however briefly, Romania. Countries like Great Britain, France, Prussia, Russia and Austria used and abused the other nations, other peoples, dangling independence and recognition like carrots to help in a shifting sea of alliances and treaties.

On the 30th of March 1856, Paris was host to a congress of international luminaries seeking to resolve the issues raised by the Crimean War. Despite technically losing the war, and despite losing all of the territory it had gained from the Ottoman Empire prior to it, Russia came out of the whole affair largely unaffected.

Of greater concern to us is that the states of Walachia and Moldavia were given a large degree of guaranteed autonomy while still being under Ottoman control. This was hardly what those swept up in the growing tide of Romanian nationalism had sought. They had been supported in their desires by the French Emperor, Napoleon III, but the creation of a united Romania was blocked utterly by Britain, Turkey and Austria (who had experienced actual rebellion in 1848 in Hungarian-ruled Transylvania, which wanted to join a united Romania). Russia was content to let the Romanians deal with the situation not wishing, perhaps, to push its luck with the other powers even for a potential allied country.

The nationalist fervour in Romania continued unabated. Pressure grew steadily and the Ottomans reacted by attempting to ‘adjust’ elections to assemblies in the two countries whose purpose was to discuss unification, resulting in a seemingly massive vote against the creation of a united Romania. This time, France, Britain and Russia stepped in, and the renewed assemblies called for unification of Walachia and Moldavia.

However, in Paris in 1858, the universal cry of the Romanians was ignored. In a botched solution that satisfied no one, the United Principalities of Walachia and Moldavia were created, still technically under Ottoman rule, with the same currency and legal systems, but forbidden from uniting.

The ridiculous situation could not continue. In the end the Romanians themselves dealt with the issue. On the 5th of January in Iasi, Moldavia, and on the 24th of January in Bucharest, Walachia, the assemblies voted for the same leader, Colonel Alexander Ioan Cuza. Despite resistance from the Austro-Hungarians, the Ottomans gave their approval to his appointment in December 1861. Fortunately for Romania, the attention of the Great Powers was on Italy at the time, and the unification went uncontested. The creation of the country of Romania was formally recognized on the 24th of January 1862, with Cuza leading it from the capital, Bucharest.

Gathering his enlightened advisors close about him, Cuza sought to implement sweeping reforms to the constitution, education, the legal systems, the army and, critically, to land and agriculture.

In 1863, the monasteries saw their land taken from them, returning nearly a quarter of agricultural land to the state in one move. The Church retained all of its buildings as well as what was declared, “a sufficiency of agricultural land to retain a just and appropriate degree of provision, and to maintain the historical integrity of ecclesiastical properties for the benefit of the Nation.” Cuza was convinced by certain of his advisors not to offer compensation, and the cries of the Eastern Orthodox Church went unheeded by the international community.

In 1864, after some reworking of the constitution to bring it closer to the French model of Napoleon III, Cuza was able to make significant inroads to ending the feudal systems that dominated Romanian agriculture. This led to a degree of political conflict with the land-owning boyars. They had come together as a conservative alliance to reign in Cuza’s more liberal tendencies. They found support, if only secretly, from some of the Prince’s direct advisors, who tipped the boyars off as to Cuza’s future plans to fully confiscate their estates. Whether this was true or not, the Agrarian Law was heavily opposed and resulted in an act that didn’t help the peasants but that allowed the boyars to become even wealthier.

The army reforms were initially well received by the military leaders. The close relationship with the French Emperor and Prince Cuza meant that French advisors and experts were very much in evidence. Despite the assistance they offered, the Romanian military chiefs were impatient to take things entirely into their own hands. They heard, through advisors close to Cuza, that there were plans afoot to place French commanders at the head of the army, though no one was clear how long this would be for. Whatever the case, Cuza lost the faith of the army commanders, something that was to prove decisive later.

Despite his best efforts, and despite the clear benefits his rule brought, Cuza found himself bogged down in political, financial and personal difficulties, most based on unfounded rumour. Things came to a head in February 1866, when he was ousted in a mini-revolution. After being forced to abdicate, Cuza went into exile. In his place, the boyar Princes ruled as a council until a new over-all ruler could be found.

The agrarian reform conflict of 1864-5 had seen Cuza lose as Prime Minister his friend and ally Mihail Kogăliniceanu, who had resigned. In his place rose other advisors, particularly Austrian-born Karl Baden. Baden, whose family had originated in Austro-Hungarian controlled Transylvania, was a passionate believer in Romanian independence. He used his own independence from the existing politics to act as go-between in all situations, though he was reluctant to take any credit for his brokering.

The coalition of Liberals and Conservatives that had gathered together, along with the military commanders, to overthrow Prince Cuza now turned to Baden. Reluctantly, he became both Prime Minister and Princely Lieutenant, vowing to give up both posts as early as possible. His elevation to Prince had become possible when it was discovered that his family traced itself back to minor royalty of the area around Târgu Mureş in the Carpathian Mountains. Baden was deeply embarrassed by the whole thing, and refused a formal investiture.

During the next ten years, as candidates for the rulership of the country were repeatedly rejected by the boyars and the rest of the council, a frustrated Prince Baden brought in further reforms, principally to education, and began an efficient and organised modernisation of the country. Of primary importance were the continuing improvements to the transport infrastructure, particularly the beginnings of a rail network. Experts and engineers from across the world were brought in to coordinate these projects, as well as to train their eventual replacements.

A great many of these improvements were paid for by unusually shrewd investment from the boyars. Baden’s desire for further land reforms saw some slight improvements in the conditions for the peasantry, but only when the State balanced this with concessions regarding ownership of the newly opened mines that began to appear, as hired engineers and surveyors from across Europe started to open up the natural wealth of the country. This wealth was to pay for a round of diplomacy and a quiet military build-up that was to have far reaching effects.

Romanian diplomats continued to be active in France and Russia. This was to be expected. More unexpectedly, Romanian diplomats also became more prominent in Bismarck’s newly created Germany. Considering the growing problems between France and Germany, the creation of the Three Emperors’ League in 1872, which did nothing to address the Transylvanian issue, and the clear inevitability of another war between Russia and the fragile Ottoman Empire, the position of open neutrality that Romania was taking might have seemed odd, save that it allowed all parties a diplomatic ‘delivery boy’ from time to time.

In the end, the true reasons for the diplomacy were to become brutally apparent. With the Austro-Hungarian government walking on eggshells to avoid antagonizing Bismarck and the expansionist German Empire (not to mention the German’s allies, Russia), a growing crisis in the Balkans saw Bulgarians seeking freedom from the Turks. With the Russians doing what they could to help the Bulgarians, tensions rose further. Revolts all across the Ottoman-held Balkans were cruelly put down and war exploded in the region. After negotiations with Austria-Hungary, Russia entered the war in 1877, moving its troops freely through allied Romania.

Now the Romanians made their move.

All across Hungarian-held Transylvania, the Romanian population moved to open rebellion, assisted by sudden, well organized and supplied partisan attacks. Simultaneously, Romanian troops advanced to assist their brothers and sisters, sweeping across the mountain passes. Slavic nationalists reacted to the growing chaos by staging protests that tied up Austro-Hungarian manpower. The German Empire too had been ready. Bismarck used the ‘unexpected situation’ to generously move to assist the beleaguered Hapsburgs in ‘maintaining order’.

Russia won the war against the Turks, and the Treaty of San Stefano saw Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Romania declared fully independent. With the rest of the international community up in arms over perceived Russian and German gains, the Hapsburgs had to be content to see the German ‘peacekeeper’ forces withdrawn. In a Congress in Berlin in July of 1878, Romania saw its borders confirmed as the fully reunified country was recognised by the international community (even by an unhappy Hapsburg delegation).

Russia had absorbed Moldova and Bessarabia, and so the border between Russia and Romania was set along the river Prut down to the Danube delta. This would be the case for many years, until Tsarist Russia fell and, in the ensuing chaos, the territory was regained for what had been Romania. The borders with Bulgaria and Hungary were argued back and forth, with the Hungarian border being thrashed out under the watchful eye of Bismarck in Berlin. Romania had to concede some territory on all sides of its new borders, particularly in the north, but the overall gains were sufficient to offset local complaints. The eventual Treaty of Berlin, signed on the 13th of July, set it all in stone.

Prince Baden suddenly found himself being edged toward being crowned King. He was a hero to the people of Romania, be they boyar or peasant, Conservative or Liberal. Once again, he accepted reluctantly, but only on the condition that there be further political reform. Also, he announced that, in the spirit of the new age, that the united country should have a new name –Promethea.

Such was his popularity that Baden’s flight of fancy was passed. His political reforms too were swept through, even the often controversial reorganizing of the 70 plus administrative counties down to a more manageable 41. They saw a Council of Advisors established, two thirds of whom were elected by the parliament and the rest appointed by the King. The Council would work with parliament to enact the wishes of the King in accordance with the wishes of the voting people, few though they were. The King promised that he would not interfere with the parliament, and indeed took himself off to his ancestral estates at Târgu Mureş. There, he founded a third university in the country, after those of Iasi and Bucharest.

In Promethea, things began to move apace. The King was at pains to promote the country to the world as a politically neutral place devoted to learning and scientific advancement. It would embrace the new industrial age, and would sponsor science and engineering developments and research. Grants were given to successful applicants from across Europe and even from America. Conferences and exhibitions were held, and Promethea became a shining light in a Europe increasingly overshadowed by a worsening political situation.

The King, backed by the Council and by parliament, was forced to increase military spending and development. Promethea had declared itself neutral, but it had to maintain its borders to protect that neutrality and to protect its people. It had to become more self-sufficient. To this end, both agriculture and industry were nationalised in the early years of the 20th Century. Acts of sabotage and espionage sponsored, the King told his astonished, angry people, by foreign radicals and jealous governments with expansionist agendas, caused a tide of Promethean national pride and determination. The military and the Council were voted more powers still. Finally, after a plot that saw an assassination attempt on the King during a session of parliament, the parliament itself was dissolved permanently, with all legislative powers being passed to the Council on the 8th of June 1902.

It was done.

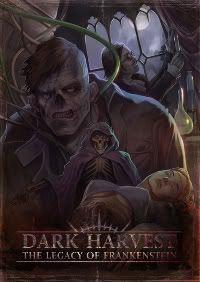

Promethea was now a military state, run by the King and his Council. The rest of Europe couldn’t care less, caught up as it was in political crisis after political crisis as the Great Powers moved toward World War. What did they care if the reclusive King of neutral Promethea declared himself not in fact to be Karl Baden, but in fact one Victor Frankenstein? What business of theirs was it if the ordinary people of Promethea had become lowly serfs once more, toiling in the fields and factories owned by their Council and boyar masters? Well, Europe, indeed the world, was to care very greatly indeed.

Beginning as rumour within the scientific community, becoming news and then a protected secret, information on Frankenstein’s dark legacy began to reach the governments of the world. Whereas previously Bucharest had been host to development conferences, now these were moved to Promethea’s de facto capital – the growing town of Târgu Mureş in the Carpathian Mountains. There, under tighter security, the visiting scientists, inventors, engineers, industrialists, politicians and dignitaries attended the usual round of conferences, discussions, exhibitions and parties.

However, gone were the tours of the countryside, the hunting trips, the boat and train rides used to proudly show off the developing country. Now, ingress into Promethea was restricted to the port of Constanta on the Black Sea, the port of Galaţi on the Danube in the east, the overland route through Hungary to the border crossing at Bors, near Oradea, and the route along the Danube to Orşova, beyond which boats were banned. Provided transport at the official pick up or transfer points was generally luxurious but regularly windowless.

All other border crossing points became closed military outposts of varying size and regular, efficient, heavily armed patrols prevented anyone getting in or out. The same was true of the ports, where all contact between visiting ships and the local population was suddenly forbidden. This occurred at the same time as foreign observers reported seeing the Promethean fishing and merchant fleets burning in their ports. The whole country was utterly isolated.

Despite this, information and the occasional refugee got out. Generally speaking, the fantastic stories and terrible rumours were publicly dismissed by governments. Privately, those same governments were both concerned and intrigued. Trade and contact with Frankenstein’s people brought enormous benefits, and having a reliably neutral country in the otherwise fiery and unstable Balkans was no bad thing, particularly as a check to Russian and German expansionism. However, the treatment of the Promethean people was the cause of some limited consternation amongst certain campaigning groups and was occasionally an embarrassment at a diplomatic level. Of deeper concern to the world governments were the scientific, military and medical advances that Promethea was rumoured to be withholding.

Some of them were obvious. Promethean soldiers carried fearsome-looking firearms the likes of which were not seen anywhere else. The soldiers themselves, while as disciplined and ordered as any other army, were somehow different. This was particularly the case with Frankenstein’s hulking personal guard who, like the king himself, were rarely seen. The trains used by the Prometheans were clearly more advanced than those in the rest of Europe, and there were rumours of flying machines and other exotica.

Soon, espionage and counter-espionage were the order of the day at all events hosted by the Prometheans. Along the borders, infiltrators were sent in, though very few returned. As a result, the borders of Promethea quickly became fenced, walled, moated and entrenched affairs, strung with barbed wire and dotted with watchtowers and military bases. It was as though the Promethean aristocracy had been looking forward to the excuse to shut themselves away even more.

It is now 1910, and Promethea is an utterly closed place. The rest of the world is desperate to discover what goes on there. They are nowhere near as desperate as the people – the proud, hardy Romanians, who want their country back, who want their lives back. Locked in a near-medieval world, what can they do against the might of the Promethean aristocracy, the utterly loyal military, and the terrible creations of Frankenstein’s dark science?